South Sudan becomes the world’s newest independent nation on 9th July. Within days it is expected to be the 193rd member of the United Nations.

Very few countries have been born into the atrocious conditions of South Sudan, and in the coming months and years, the name of the country and the problems of its people will become known far and wide.

South Sudan has emerged into nationhood after more than 20 years of bloody civil war in Sudan in which upwards of two million people are estimated to have been killed and another four million turned into refugees.

Over the last six years Sudan limped through a transition mandated by a Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed in 2005 and brokered by South Africa under its then President Thabo Mbeki. A key promise of the agreement was that a referendum would be held allowing people from the South to choose between remaining part of Sudan or forming a new state. The referendum, held on the 9th of January, resulted in a resounding demand for a separate state to be named the Republic of South Sudan.

During the six-year period, there was no full scale war, but plenty of bloody skirmishes.

And, the skirmishes do not look set to end with South Sudan’s independence. Indeed, the United Nations is already contemplating maintaining a 7,000 strong peacekeeping force in South Sudan after the new country is admitted to the UN membership. Deep rivalries between the Muslim North and the Christian South continue to cast a pall of gloom over South Sudan’s separate status.

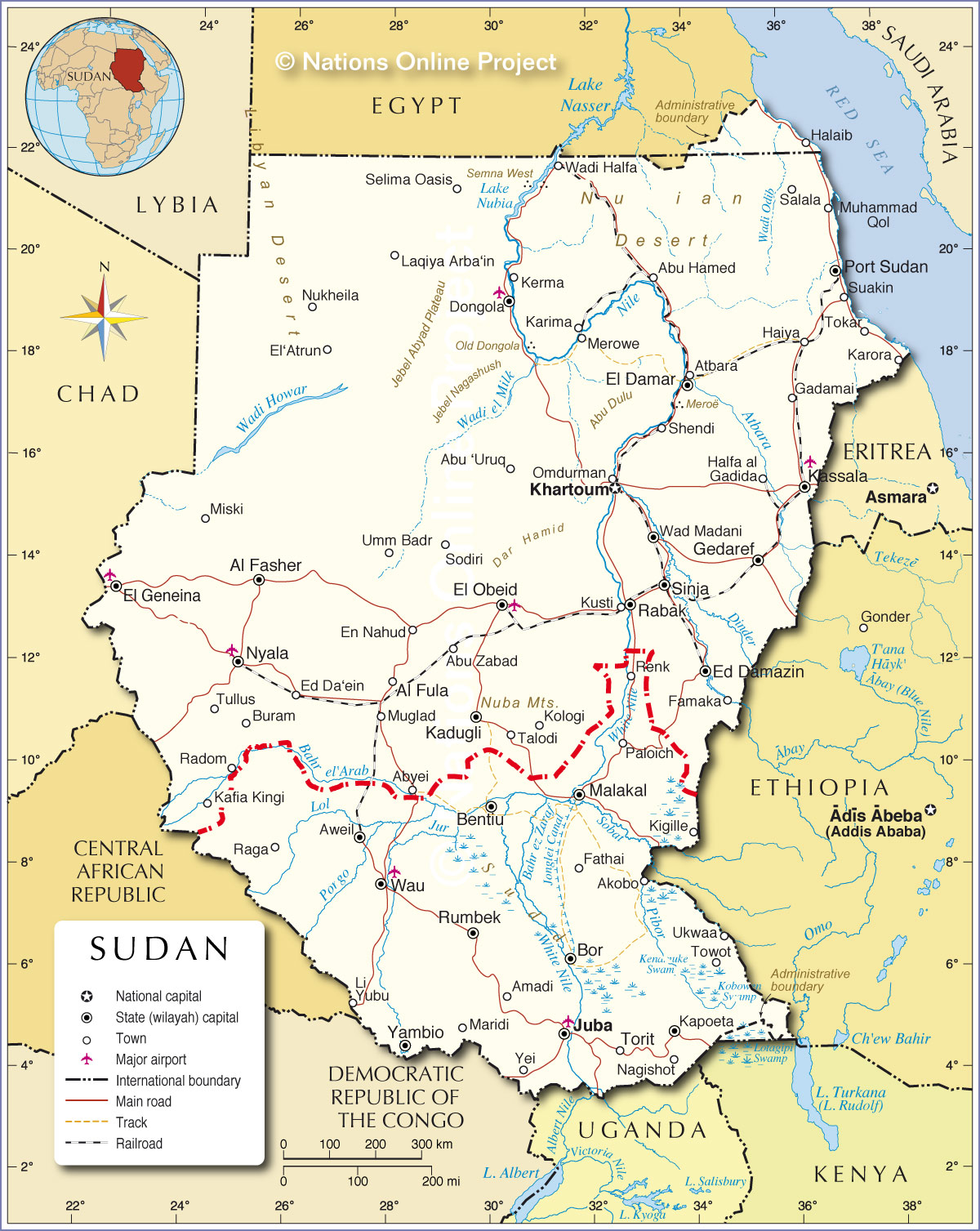

While the rivalry can be explained in part by the religious differences between the inhabitants of the two Sudans, it is oil that now lies at the heart of the trouble. The oil-rich region of Abyei is nominally in the South, but has been seized by the North. This unresolved issue will pester the relations between the two countries and will be the source of their continuous hostility, particularly as land-locked South Sudan’s oil will have to be exported through the North.

Until the division of the country and the Republic of South Sudan’s independence, Sudan was Africa's biggest country. Sudan will now lose a third of its land mass and 80 per cent of its oil reserves.

But, if that portends grave economic difficulties for Sudan, the signs are just as alarming for the Republic of South Sudan which begins its independent status with an 85 per cent rate of illiteracy among its eight million people, and a huge shortage of capacity in its public services to deliver goods and services. Further, after years of neglect by the government of Sudan, the new Republic has less than 100km of paved road; 90 per cent of the people live on less than $1 a day; and Juba, which will become its capital, is one of only a few places with electricity. Reports indicate that most areas have no medical services.

These are hardly the most attractive conditions in which to enter a highly competitive international community. Nonetheless, after 20 years of bloodshed, the people of the new Republic must be looking to the future with some hope – if only on the basis that anything would be better than what they have suffered so far.

South Africa, which god-fathered the 2005 peace arrangements that led to the division of Sudan and the creation of the new Republic of Sudan alongside the old, and now weakened, Sudan, is keen to continue to play a role. On the eve of the Republic’s independence, South Africa's International Relations Minister, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, said, "South Africa views the restoration of peace, security and stability in the Sudan positively in the Horn of Africa region, and on the continent as a whole. Any instability in the Sudan impacts negatively on the nine countries that it shares a border with."

Nkoana-Mashabane said South Africa has already trained more than 1,500 South Sudan civil servants and diplomats through its various programmes, including Diplomatic Training, to ensure the attainment of capacity building and skills transfer for the betterment of South Sudan.

A growing number of South African companies like MTN - which has acquired a majority shareholding in a local mobile phone operator called Areeba - and SABMiller (Southern Sudan Beverages Pty Ltd), which established a brewery in South Sudan, are also showing interest in the new country.

Many more investments of this kind will be needed to develop South Sudan’s economy notwithstanding its oil resources. Agriculture, in particular, will have to be developed to give the country food security especially as it will be entirely dependent on its neighbouring states for the transportation of almost all of its trade with the outside world. Few new states have faced the developmental challenges of South Sudan.

The new Republic can also expect an influx of South Sudanese who will be displaced from the North. Already persons born in South Sudan who have been working in the Sudanese public service have not only been dismissed from their jobs, they have also been deprived of their citizenship. Recent UN reports estimate that between 400,000 to 800,000 people will likely migrate back to the South.

In addition to applying for UN membership and membership of the African Union, both of which are expected to be automatic, South Sudan is also expected to apply for membership of the Commonwealth, an association of 54 nations comprising Britain and its former colonial possessions or protectorates for the most part. The official languages in South Sudan are presently Arabic and English, but the government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit has indicated that English will be the only official language.

South Sudan would benefit enormously from membership of the Commonwealth because of the association's capacity for advancing development and for providing technical assistance to build capacity in its developing member states in a range of areas including governance, financial management and managing trade. However, the new Republic would first have to commit to upholding Commonwealth values which include democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

Undoubtedly, the government would need expert help to establish the machinery to uphold these values, and help would be forthcoming from many Commonwealth civil society organisations, making membership of the Commonwealth possible.

Such membership would considerably enhance the world’s newest country to deal with the enormous challenges that accompany its birth.